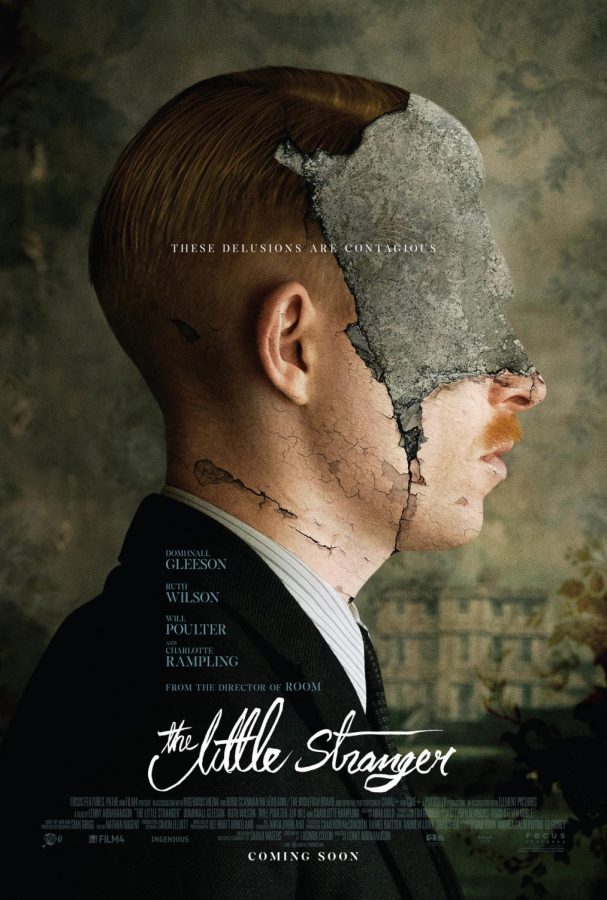

“The Little Stranger” Review: A Cautionary Tale of Class

Period pieces seem to feature larger-than-life settings that risk overpowering more subtle performances. In the case of “The Little Stranger,” however, the captivating, decaying Hundreds Hall estate elevates its inhabitants’ interactions as they navigate the dreary halls, complex relationships and passage of time.

On the surface, “The Little Stranger” gives off the air of gothic horror, but director Lenny Abrahamson (also known for 2015’s “Room”) chooses to go a more nuanced route, illustrating the horrifying psychological effects of social hierarchy. The plot doesn’t burn slowly, per se, but rather gradually freezes over, becoming more and more chiling as it nears its climax. The slow accumulation of dread is helped enormously by Domhnall Gleeson’s eerie performance as the seemingly detached Dr. Faraday.

Predominantly a tale based on memory and time, it makes sense that the film opens with a nostalgic Dr. Faraday returning to Hundreds Hall, the site of his most precious childhood memory and where his mother had worked as a maid years ago. For ages, he has held onto a childlike fascination and obsession with the upper class and the Hall’s picturesque inhabitants, the Ayreses. Once Faraday arrives, however, he finds the once glorious mansion and Ayres family in rapid decline. Faraday is directed to treat housemaid Betty (Liv Hill), who is petrified of a diabolical presence that haunts the house’s halls.

The main goal of the presence, seemingly, is to rid the estate of its residents, including the once-illustrious Mrs. Ayres (Charlotte Rampling) and her children: the intelligent, isolated Caroline (Ruth Wilson in a standout performance) and scarred veteran Roderick (Will Poulter). The family and Faraday largely ignore the evil phantom — thought to be the first Ayres daughter Susan, who died as a child — for the majority of the film, and Abrahamson turns the narrative to focus on the budding relationship between Faraday and the Ayreses, most particularly Caroline.

Gleeson’s Faraday has a chilling, obsessive air about him; slowly but surely, as he becomes more involved in the family’s dynamics, he falls for Caroline. Even though his intentions seem pure at first, they become increasingly troubled as his obsession with the idea of the house and aristocracy predominates his every action. Abrahamson emphasizes Faraday’s fixation with the past with well-placed flashbacks to a young Faraday (Oliver Zetterstrom) haunting the Hundreds’ halls decades earlier. As he’s reminded of his lower social standing time and time again, Gleeson expertly exudes a simmering frustration behind a mostly flat disposition.

Faraday is tormented more by the concept of the Ayres family and what could’ve been than he is by the actual ghost. The brief moments of terror do come — albeit after the film’s slow parts drag out for too long — and it is a slow crescendo until the film’s pinnacle confrontation with the spirit. Every move Abrahamson makes is calculating and purposeful, building up the tension, but the first three quarters’ dragging progression risks losing its viewers’ attention.

“The Little Stranger” is chock-full of blatant symbolism; the Hall’s state of decay personifies Faraday’s fragmented mind. His increasingly unhinged and unreliable point of view grounds the film, thrilling to watch despite its lack of jumpscares. However weighed down it is by a sluggish tempo, “The Little Stranger” is worthy of a B+ for its tenacious artistry and performances, and its underlying motif of the dangers of the class system gives it just the right amount of profundity.

Senior Morgan Pryor is a film enthusiast, visual artist and regular Comic-Con attendee. She plans on going to college to study studio art and journalism.